Imagine if you had the ability to choose any of the issues under the agricultural sustainability umbrella and could then run computer-generated outcomes according to variables of your own choosing. This kind of modelling is being done with weather, urban growth, traffic, just about everything. Let’s take a look at a more human kind of modelling—the art of fiction. What can fiction tell us about sustainable food systems? Deciding to find out, I chose three novels (set in the past, the present, and the future) as imagined by perceptive, articulate, and compassionate story tellers.

Past: The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck

The Grapes of Wrath is perhaps at the headwaters of fiction, illuminating environmental, social, and economic problems. Although Steinbeck does not offer a definitive solution to the challenges he presents, he paints a clear, moving tale that is deeply human. It is the story of competing, conflicting, struggling forces, and it holds an important message for us today.

The Grapes of Wrath is perhaps at the headwaters of fiction, illuminating environmental, social, and economic problems. Although Steinbeck does not offer a definitive solution to the challenges he presents, he paints a clear, moving tale that is deeply human. It is the story of competing, conflicting, struggling forces, and it holds an important message for us today.

The Dust Bowl of the 1930s was a perfect storm of a drought and farmers’ failure to apply dry land farm methods that prevented erosion. Rapidly developing mechanized farming machinery was put to use. Extensive plowing loosened the topsoil, which then turned to dust and blew away. But Steinbeck doesn’t stop there. He illustrates social and economic consequences including food insecurity, corporate land grabs, exploitation of migrant workers, and hopeless poverty.

Steinbeck contrasts the greed and self-interest of the landowners with the generosity and humanity of the poor. He points out these cyclic patterns as if to say, “It’s not right, but there it is.”

What can we learn? We know greed and hubris can bring down empires. There is not likely to be a Kumbaya moment anytime soon. Perhaps the message is that we can no longer afford complacency. We can’t wait until ecological disaster ushered in by climate change is upon us to prepare ourselves for a paradigm shift of agroecological responsibility. “Bigger might not always be better,” Steinbeck seems to be saying, “and more might not ever be enough.” Humanity will benefit from systemic changes to encourage local, sustainable, affordable, healthy food. The economic and social divisions will perhaps then begin to heal. The key, the author suggests, is to learn to live with nature instead of attempting to tame or conquer it.

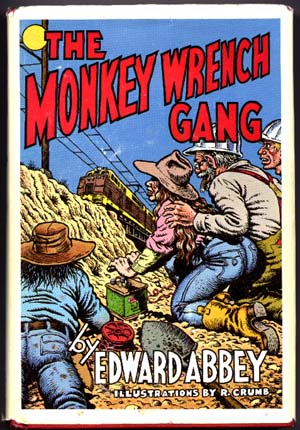

Present (Approximately): The Monkey Wrench Gang by Edward Abbey

The Monkey Wrench Gang is an impassioned homage to the desert; in particular, the American Southwest. Abbey has a striking ability to call forth detailed description of the landscape, which is not lifeless at all, but a stunning, magnificent, national heritage that must be protected at all costs. Even if that means breaking the law. The author of Desert Solitaire, Abbey was a ranger for the National Park Service and his knowledge of flora and fauna is breathtaking.

The Monkey Wrench Gang is an impassioned homage to the desert; in particular, the American Southwest. Abbey has a striking ability to call forth detailed description of the landscape, which is not lifeless at all, but a stunning, magnificent, national heritage that must be protected at all costs. Even if that means breaking the law. The author of Desert Solitaire, Abbey was a ranger for the National Park Service and his knowledge of flora and fauna is breathtaking.

Further evidence that fiction influences reality, The Monkey Wrench Gang was the book that inspired Earth First, real-life sabotaging ecoactivists who use guerrilla tactics in defense of the land. ‘No Compromise in Defense of Mother Earth!’ is their slogan.

Abbey believed nature was better off without people. Any intervention was a despoliation. The Monkey Wrench Gang is made up of memorable and quirky characters reminiscent of A Confederacy of Dunces. At times slapstick and funny, at other times it is moving and profound. Abbey, an articulate and graceful writer, tells the story of this oddly-matched group of strong personalities (one is a medical doctor who likes to burn down billboards) who sabotage huge strip-mining equipment, clear-cutters, and bridge builders, the last being an obvious symbol of human growth and expansion.

What can we learn? The message here is loud and clear. We should reject complacency and embrace activism to prevent the destruction of natural resources. “Talking about it,” Abbey seems to say, “is useless. Action is required.”

Perhaps Abbey is showing radical or violent behavior to dramatize that action is necessary. In fact, no one is killed in the book. Abbey is promoting activism, not terrorism. Perhaps Abbey said it best: “At some point we must draw a line across the ground of our home and our being, drive a spear into the land and say to the bulldozers, earthmovers, government and corporations, ‘thus far and no further.’ If we do not, we shall later feel, instead of pride, the regret of Thoreau, that good but overly-bookish man, who wrote, near the end of his life, ‘If I repent of anything it is likely to be my good behavior.’”

Future: MaddAddam Trilogy by Margaret Atwood

Margaret Atwood is a recognized writer and environmentalist who often indulges in speculative fiction, a comprehensive category that includes fantasy, science fiction, and just about every other kind of imaginative fiction.

Margaret Atwood is a recognized writer and environmentalist who often indulges in speculative fiction, a comprehensive category that includes fantasy, science fiction, and just about every other kind of imaginative fiction.

In the MaddAddam Trilogy, Atwood takes on a flock of issues, primarily transgenic engineering (i.e. GMOs). But that’s just a starting point—she scrutinizes megacorporations, insatiable consumerism, avaricious capitalism, and the commodification of nearly everything.

In Atwood’s future, free markets have created global anarchy, first destroying governments, then communities and, finally, putting all life on the planet at risk. Science has become a slave of commerce and commerce is, in turn, the servant of limitless greed and unchecked exploitation of human hubris.

This tale unfolds in three books (Oryx and Crake, The Year of the Flood,, and MaddAddam), as they tell of the cataclysmic self-destruction of humanity (by virus) and Homo sapiens evolution into a new species, a mélange of genetically-engineered traits (“a GMO hodgepodge of all the cuddliest and most peaceful parts of the animal world. They blush blue when they go into heat, their urine smells lovely, they live on grass, they purr, and they sing like birds. And they have been designed to eschew the violence of Homo sapiens—they have no sexual jealousy, no hierarchy, and no modesty about their bodies”).

Ironically, genetically-engineered humans are the next big evolutionary step for humanity. The corporations are gone, but what survives is an engineered-but-sustainable alternative. Whether it’s a step forward is unknown and unaddressed. Important questions remain: What has been sacrificed? Is it possible GMOs will ultimately be absorbed, balanced, and at one with nature?

It’s not all bad for humanity. “The Gardeners” are a group of people who have intentionally dropped off the grid. Disgusted by the values of mainstream society — especially GMO food and rampant consumerism — they become urban farmers. They’ve had enough of food politics and class warfare and break away to form their own community. When the epidemic comes, many Gardeners survive. Well-acquainted with the urban ecosystem and not dependent on the grid, they are able to defend themselves.

What can we learn? Perhaps it’s that nature will win in the end. We might be a blip on the geological timeclock, barely there long enough to leave a shadow of a memory. “If you want to last a bit longer,” Atwood seems to suggest, “it’s time we stop relying on technology, start learning agricultural self-sufficiency, and take political responsibility to assure the well-being of all animals and humans.”

It’s Unanimous

What these writers of three very different books share are a deep respect and love for the land, for nature, and for life. Their books are cautionary tales as well as introspective assessments of ourselves. Fiction allows us to see the big picture while living vicariously through realistic, relatable characters; these books create insight into the way we live, what we hope for, and possibly what we can expect.

Further Reading

Growth of the Soil by Knut Hamsun. Winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, the story follows a family over generations as they make their living off of the land and struggle against the corporate interests of the copper mining business.

The Price of Land in Shelby by Laurie Alberts. Situated in fictional Shelby, Vermont, the story tells of a family’s struggle with poverty. On what used to be a farm but since divided into “executive lots” where rich Flatlanders build expensive homes, the Chartrain family now lives in trailer homes and broken down houses with yards filled with junk. What sustains their thirty-year struggle is their deep connection to the land.

The Jungle by Upton Sinclair. Set in the early 20th century, the story tells of the dangerous working conditions of the meat packing industry. These jobs were typically held by impoverished immigrants who were at the receiving end of inhuman, destructive, unjust, and violent treatment by American Capitalists. Rich companies failed to have social programs, or take safety precautions, but willingly sold diseased meat to an unsuspecting public.

For Kids: The Seed Savers Series by S. Smith. “What if gardening was illegal?” is the question asked in Treasure, the first book in a series. Climate change has ravaged the planet and processed food is the only food available. The young hero, Clare, meets an old woman who introduces her to real food and, more importantly, seeds. Clare and her brother flee when the authorities arrest her mother because of Clare’s illegal tomato garden. The story follows them as they cross the country on bicycles in search of a place where they can garden legally and freely. Addresses real issues, including corporate seed monopolies and the importance of healthy food.