The Environmental Imagination: Applying the Lessons of Environmental Humanities

As Spring washes over the landscape here in Vermont, I find myself staring at the greening through the tiny squares of the mesh screen of my window. The screen has a job to do, I realize, and that is to keep the bugs out. If I remove it I will see the loveliness of the lush forest unfettered, but black flies, mosquitoes, spiders, and countless others will find access to my living space.

As Spring washes over the landscape here in Vermont, I find myself staring at the greening through the tiny squares of the mesh screen of my window. The screen has a job to do, I realize, and that is to keep the bugs out. If I remove it I will see the loveliness of the lush forest unfettered, but black flies, mosquitoes, spiders, and countless others will find access to my living space.

This strikes me as an apt metaphor for the Environmental Humanities, a field that strives to integrate the specialization and compartmentalization of the sciences and humanities to provide a more holistic view of the environmental issues we face today. Embracing the bigger picture, however, invites critical accusations of ‘softer’ reasoning against the ‘harder’ sciences, which leads to the question: Can the humanities and arts create a more accurate vision that enable more livable and sustainable places and more effective and equitable environmental practices?

Although there is no universally-accepted definition of Environmental Humanities, there is a general consensus that it seeks solutions to sustainable global development challenges by embracing a dizzying array of interdisciplinary studies, including anthropology, ethics, archaeology, culture, economics, geography, history, languages, law, linguistics, literature, philosophy, performing and visual arts, political sciences, psychology, religion and sociology.

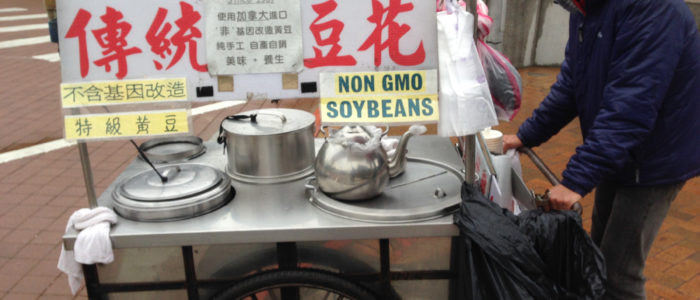

The goal of Environmental Humanities is to apply critical thinking to analyze and understand the context and developmental problems under consideration and then propose and prioritize options that could suggest possible solutions. Putting a human face on environmental issues frames and advances conversations that allow not only students and scholars across disciplinary fields access to the research methods, vocabulary, and practices of other fields, but to communicate to broader audiences, including the general public. For example, if we wanted to demystify the extent to which we use, abuse, misuse, and overuse our food supply, how might we go about communicating this?

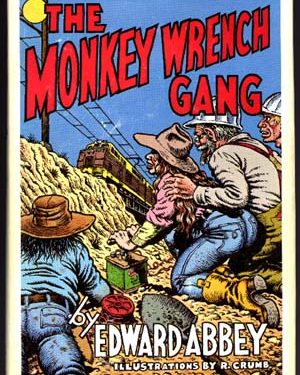

But let’s get real. Can literature, for example, affect environmental values and practices? Can a novel or poem make a more sustainable world? Many believe it can focus, shape, and respond to issues such as sustainable food, animal welfare, pollution, and global warming. Poets, novelists, photographers, playwrights, performers (note Neil Young’s new album to be released later this month with biting commentary on Monsanto), and a host of other artists are now producing works reflecting and commenting on our present environmental situation. These works are influenced and inspired by hard environmental questions about hunger, climate change, place and landscape, and pursue imaginative visions that illuminate global anxiety. In his impressive volume The Agrarian Vision, Paul B. Thompson points out that Environmental Literature allows us to “try on” various situations and scenarios. It functions as an experimental laboratory weaving the many components of the humanities and sciences into a functioning, organic whole; in short, a model for possible outcomes.

Humanities, Global Corporations, and the Environment

In a fascinating study completed late in 2014 by the British Council—a nonprofit that promotes cultural relations and education—four keys to ‘humanizing’ global development challenges were identified. When applied, these keys were recommended as effective strategies multinational corporations should use to achieve tangible solutions to environmental problems:

◆ Critical/analytical thinking, including local needs assessment and program development; application of logic and reasoning to solve complex problems;

◆ Flexibility and tolerance for ambiguity, including rapid reaction to emerging situations; adaptive approaches as new information arrives; ability to navigate program implementation when there is a lack of clarity;

◆ Communication and negotiation, including culturally-sensitive communication; ability to negotiate complex and sometimes competing relationships and objectives; and

◆ Local Knowledge, including conversant in political and administrative systems, economics, law, history, language and culture; ability to form effective situation analysis and needs assessment; and ability to deliver successful programs

Infographic credit: “British Council”

Whether producer or audience, the benefits of the interdisciplinary vision of Environmental Humanities allows us to grasp complex issues, accept cultural differences, and provide new insights into seemingly intractable environmental problems. Perhaps we can then remove the screens from our eyes and enjoy the view.