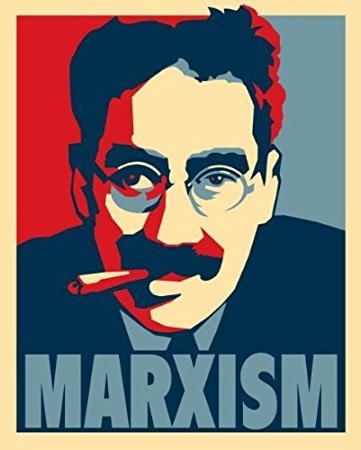

When it Comes to Food Justice, Am I a Marxist?

An interesting thing happened to me on my way to the Farm-to-Table movement. I discovered I might be a Marxist. More to the point, I found that my thinking was in agreement with some Marxist tenets, and, for a short while, I panicked. Was I really a Marxist?

An interesting thing happened to me on my way to the Farm-to-Table movement. I discovered I might be a Marxist. More to the point, I found that my thinking was in agreement with some Marxist tenets, and, for a short while, I panicked. Was I really a Marxist?

The issue at hand is food justice. If I believe that systemic changes are necessary to achieve sustainable, equitable, fair, and democratic food systems, does it follow that I am a Marxist? Words like “equitable”and “fair”sound righteous on the tongue, something akin to the old Superman series where he is introduced as “fighting for truth, justice, and the American way.” What is the American way?

Before any of these heady questions could be addressed, I sought to clarify exactly what I thought of the food production system, agricultural sustainability, and the fresh food movement in America. If I did that, I figured, I could then superimpose the definition over my beliefs and see if it fit. (If it did fit, I worried, I might have to change my wardrobe, my hair style, my passport, and god knows what else. The whole thing made me nervous, but I had to find the truth.)

Dilemma #1: Would I rather work for immediate food aid for the hungry or struggle for structural change to prevent hunger in the first place?

Attempt at Authentic Response: The word “struggle”worries me. Is that struggle as in “class struggle?” Can’t we just change the word to “effort”and call it a day? I believe I would be more satisfied working toward a permanent change, as in structural, than applying a temporary fix. While I don’t want anyone to go hungry, and I respect and admire those who are feeding the hungry, for me a sustainable solution rests in rethinking why there are so many of us going hungry and trying to find a fix that will guarantee future generations’ access to food.

Dilemma #2: According to Eric Holt Giménez, Executive Director of Food First/Institute for Food and Development Policy, and, incidentally, a keynote speaker for UVM’s 2014 Food Systems Summit, hunger is caused by “poverty and inequality, not scarcity.” In other words, we have enough food to go around, but subsistence farmers earn less than $2 per day. They can’t afford to purchase the food they grow.

Attempt at Authentic Response: OK, I’m having trouble again getting beyond the semantics. Whenever I hear the word “inequality” I think socialism. How about disparity? No matter. I agree with Giménez, the problem is economic, not scarcity. Most of the industrially-produced grain crops goes to biofuels and confined animal feedlots rather than food for the one-billion hungry. The winners here are the global food conglomerates, not the hungry.

Dilemma #3: In an Atlantic Monthly article, “How Junk Food Can End Obesity,” published in the Summer of 2013, the author David H. Freedman argued that big corporations are just giving people what they want. In effect, we should ride the horse in the direction it’s going by gradually shifting to healthier fast food. “Most of the obese in this country are not affluent and the fact that they can get a cheap junk food meal is a really big deal. Efforts to minimize that are appalling,” he said in a video interview.

By appalling, he meant the arguments by the proponents of the Fresh Food Movement. “A lot of people who are against the processed food service industry are really against capitalism,” he went on to say. “These people hate the idea of large companies controlling the food supply, they hate MacDonald’s, Monsanto, they hate how our society is structured and our economy is set up.”

Attempt at Authentic Response: Um. . .yeah! The argument that corporate America is just ‘giving the people what they want’ is a little self-serving, no? It’s like asking food production facilities who repeatedly distribute bacteria-ridden food to police themselves. Frankly, I was disappointed in the Atlantic Monthly, which enjoys a reputation for forward-thinking investigative journalism. The author went on to say, “If the goal is ‘let’s have everyone in America eat from tiny, local farms,’ then I think it’s going to be a hundred or two hundred years. And billions and billions of years of life will be lost while we’re waiting for that to happen.”

Excuse me? The goal is not to have everyone in America eat from tiny, local farms but to eat healthy, nutritious, affordable, accessible food. Is there any reason we can’t force a systemic reorganization tasking independent non-stakeholders to regulate the industry? Well, there’s no logical reason, but there are significant obstacles.

The Verdict

So what is my conclusion? While there are as many flavors of Marxism as there are of capitalism, it was with relief I found myself in the middle of the road. Yes, I do believe in capitalism — it is everyone’s right to own private property, and compete against others in the marketplace — but I don’t believe in 1 percent of the country owning 70 percent or more of the wealth.

I don’t believe in the revolving door between government and corporations, or moneyed lobbyists (legal bribers) with unfettered access to government officials. I believe capitalism should be regulated, monopolies outlawed, and a progressive tax system instituted that distributes power representative of the people, not of the wealthy, privileged, or entitled.

In the end, it doesn’t matter what I call myself. What does matter is my attitude toward change. Many people argue or believe that lasting change cannot come without a total failure of existing structures; a social, economic, and political unravelling or breakdown of current systems.

I disagree.

It is possible to achieve food security, justice, and sovereignty by the slow and steady convergence of the efforts from strategic alliances between the disparate groups of the food movement. Once unified, it is possible they will erupt with the same game-changing intensity as the civil rights movement, feminism, and the gay rights movements.