To Label or Not to Label

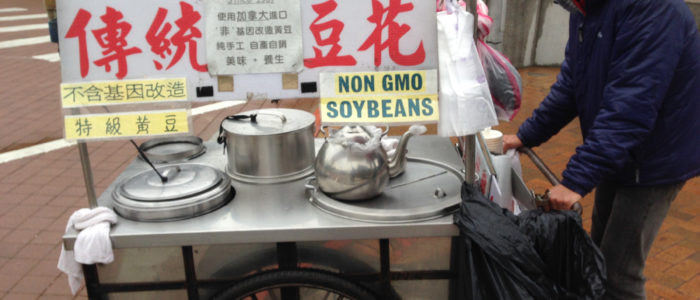

As the debate rages on between those who want GMO food products to carry labels and those who don’t, a larger question looms quietly in the background: does access to information make a difference?

As the debate rages on between those who want GMO food products to carry labels and those who don’t, a larger question looms quietly in the background: does access to information make a difference?

An escalating number of lawsuits by the Grocery Manufacturers Association, Snack Food Association, International Dairy Foods Association, and National Association of Manufacturers are challenging Vermont’s Act 120, which requires labeling of GMO foods sold at retail stores in Vermont. A decisive victory allows the winner to claim the moral high ground and establish indisputabe authority.

The battle lines are clear. Monsanto, a leading manufacturer of GMO seeds, is against mandatory labeling: “We oppose current initiatives to mandate labeling of ingredients developed from GM seeds in the absence of any demonstrated risks. Such mandatory labeling could imply that food products containing these ingredients are somehow inferior to their conventional or organic counterparts.”

The State legislature of Vermont, however, which has approved mandatory labeling of GMOs, feels otherwise: There are “conflicting studies assessing the health consequences of food produced from genetic engineering; Genetic engineering of plants and animals may cause unintended consequences; FDA relies entirely on safety studies submitted by manufacturers…” Consumers, they conclude, are “left in the dark about whether the food they purchase was in fact produced with genetic engineering.”

Both are convincing arguments. Both are invested in the rectitude of their arguments. But does labeling really make a difference on consumer behavior?

The late Donella Meadows says that it does. She offers the following example: “There was this subdivision of identical houses, the story goes, except that for some reason the electric meter in some of the houses was installed in the basement and in others it was installed in the front hall, where the residents could see it constantly, going round faster or slower as they used more or less electricity. With no other change, with identical prices, electricity consumption was 30 percent lower in the houses where the meter was in the front hall.”

The fact that electricity usage was clearly visible reduced consumption. Well, OK, that makes sense. If I can see a meter in progress, it makes a difference. But GMO labelling is static, a printed label. Meadows states that access to information at the right point makes all the difference. “Missing feedback is one of the most common causes of system malfunction.”

Theory is one thing; history is another: In 1994, it was estimated that trans fats caused 20,000 deaths annually in the US from heart disease. Yet it wasn’t until January 2006 that the FDA required food companies to list trans fat on Nutrition Facts and some Supplement Facts labels. Despite years of mounting scientific evidence that trans fats were unhealthy, and even dangerous, food manufacturers such as Crisco maintained trans fats were “generally recognized as safe.”

Interestingly, the story doesn’t end there. On June 16, 2015, the FDA rejected the argument completely and set a three-year deadline to remove all trans fats from food. “Removing [trans fats] from processed foods could prevent thousands of heart attacks and deaths each year.”

Labeling may not be the end-game, but a step in the right direction. It might turn out that GMOs are perfectly fine. Or it might turn out that mounting evidence paves the way for limited or complete removal of GMOs from our food system. If, as Monsanto asserts, labeling will imply an inferior product, then all that would be lost is profit. (However, since GMOs are associated with lower food prices, it is questionable how much profit would be lost.) On the other hand, if labeling proponents are right, how many lives would be saved from “unintended” consequences?

Monsanto is losing the battle for public-perception mindshare. In a recent poll by Pew, 88% of scientists who belong to the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) agree GMOs are “Generally Safe” to eat; however, only 37 percent of the public agrees (25 percent said they’d never heard of them).

So where does that leave us? We’ve weighed in with food manufacturers, label proponents, the State of Vermont, a systems theorist, scientists, and the public, but what about that most venerable of institutions, Consumer Reports? The magazine and its team of analysts, researchers, experts, and scientists are perceived as free of institutional, corporate, and political influence. Here’s what Consumer Reports had to say about GMOs:

1. No evidence of harm isn’t the same as saying they’ve been proved safe.

2. “The contention that GMOs pose no risks to human health can’t be supported by studies that have measured a time frame that is too short to determine the effects of exposure over a lifetime,” says Robert Gould, pathologist and president of Physicians for Social Responsibility.

3. Genetic modifications can introduce previously unseen allergens and toxins.

4. The FDA does only “voluntary” reviews, which means that the US doesn’t require safety testing on GMOs.

5. Genetic modifications such as glyphosate (Roundup) resistance are harmful for the environment, creating a generation of weeds that then evolve to become resistant to glyphosate themselves.

Common sense dictates to err on the side of caution. If, as Donella Meadows points out, “There is a systematic tendency on the part of human beings to avoid accountability for their own decisions,” and if this is borne out by historical precedent, and if GMOs are as healthy as their manufacturers claim, then it makes good sense to urge the FDA to require GMO labeling. And why not? It’s better to be safe than sorry — for our sake, for our childrens’ sake, and for future generations.